Cori Thomas, author of LOCKDOWN, talks about the realities of her volunteer work in prisons and how the vulnerability of the incarcerated people she met inspired her to put her own life story into the play. Read on to learn about Cori’s past, who inspired the characters in LOCKDOWN, and more.

by Katie Stottlemire

Cori Thomas

It was as if everyone that I met at the prison shared their DNA with me which ends up woven throughout the fabric of the play. The men were all so gracious and open, I felt it only right that I put myself in the play also.”

KATIE STOTTLEMIRE: LOCKDOWN centers completely around the experience of an imprisoned Black man, Wise, and the volunteer who works with him, Ernie. Many people may be unaware of the actual lived experience of those who spend most of their lives imprisoned. As a volunteer at San Quentin State Prison, you likely have a greater understanding of the lives of the imprisoned. Did volunteering change your understanding of the lives of the imprisoned?

CORI THOMAS: Absolutely. I don’t have lived experience, but I can say with confidence that, by now, I know more about the day-to-day routines and struggles of the incarcerated than many. I have volunteered for many years now and so I have had the opportunity to observe and get to know not just the people but their details. My initial introduction into the prison was with a podcast producer who had hired me to write narration. (The podcast did not even end up happening.) Walking into the prison for the first time, I had no experience or understanding about anything beyond what I had read and seen in the media.

I had low expectations about the caliber of people I would meet and left that day ashamed of myself. Meeting the men there and seeing how inaccurately they and their lives have been portrayed made me want very much to share what I had learned with those who don’t know. I began volunteering at the prison which has changed my life. The prison, the people housed in prisons in this country, and the unjust system that keeps many of them there their entire lives has become one of the most important causes to me. My initial visit to the prison, happened to also coincide with a commission from Daniella Topol at Rattlestick Theater to write a play about whatever I wanted. I felt this was my opportunity to do what I could to try to change the existing inaccurate image.

KATIE: So, it seems like your volunteer work influenced the writing of LOCKDOWN?

CORI: It is totally responsible for everything about it! It’s a long story, but I’ll try to give the Readers Digest version here: My initial visit exposed to me my own ignorance about prison which continued as I began writing a terrible play for the Rattlestick commission, about a man sentenced to die on death row. One two-hour visit to a prison is not adequate playwriting research, so I was reading everything I could get my hands on and watching films and documentaries but I still wasn’t hearing the voices of the men and understanding their routines in a way that made me feel I could properly write about them.

Then two things happened that feel almost miraculously fated: I won a prize from the Lipman Family Foundation via New Dramatists where I am a resident playwright, which gave me a generous amount of money earmarked for travel expenses connected to research for a play, and I received a call from a supervisor at the prison asking me if I was interested in working with one of the men I had met that first day, Lonnie Morris. I said “YES!” I live in New York, and San Quentin is in California, but I have relatives nearby, so this prize money gave me the luxury of flying back and forth and spending weeks at a time as I was writing.

The prison was not at all aware I was writing a play. I was working with Lonnie on media projects for his violence prevention program, No More Tears SQ. By then, Lonnie had been incarcerated for almost forty years. Because I would be flying from New York for only ten-day to two-week visits every month or so, instead of the usual 2-3 hours a week awarded volunteers, I was given 8-10 hour a day access, 7 days a week in the prison to work side-by-side with Lonnie. I also met many other “lifers” incarcerated alongside him.

As we began to work, Lonnie told me his story and I suddenly realized that while he was not on death row, he and most of the men I was getting to know were just as likely to die in prison as those sentenced to death. I learned that it was almost impossible to be granted parole and that society, and the system, does not seem to want to accept that a person can change. I told Lonnie about my death row play and he politely told me it sounded awful. I knew it, but yikes. So, I asked if instead I could write a play about him. He said that was not allowed without permission. So then, I said, “Suppose I write about you but I don’t tell anyone I am writing about you. I’ll give everyone different names,” etc.…And that’s how it started. That’s LOCKDOWN.

I wanted to absorb and understand the environment and spent so much time at the prison, one of the men began calling me “Cousin Cori.” We both share the same last name; no relation. Soon, everyone was calling me “Cousin Cori.” They still do. Lonnie Morris, who the character Wise is about 90 percent based on, read every draft to make sure I was accurate. Everyone I got to know at the prison was generous answering questions. They all shared their stories when I explained that I wanted to honor them and make sure that every detail was correct. One man began to give me prison slang vocabulary lessons, another gave me a list of rappers to listen to so that I could accurately write the rap, and so forth. I wrote it, but I could not have done so without their help and input.

KATIE: It’s incredible that you were able to take the time to really tell the lived experiences of those men as truthfully as possible, and it paid off: LOCKDOWN is a painfully accurate portrayal of what the life of someone who is imprisoned can be. Most of these characters are dealing with profound loss, whether it be in the form of losing a person or losing one’s freedom. Oftentimes, loss comes from a lack of closure. Both Wise and Ernie seem to not get the closure they deeply desire, yet they seem to have found some healing at the end of the play. What encouraged you to explore loss in such a vulnerable way?

CORI: It was as if everyone that I met at the prison shared their DNA with me, which ends up woven throughout the fabric of the play. The men were all so gracious and open, I felt it only right that I put myself in the play also. As I explored what brought them there, I began to explore where I was too. I realized that I was still mourning the sudden loss of my husband of 19 years, three years before. Like Ernie in the play, after my husband died, I found myself unable to write. It was only after going to the prison and meeting Lonnie and others and hearing their stories and realizing that these amazing human beings might never leave, my need to write was re-ignited. And my enjoyment of writing was awakened again.

It is ironic that being amongst people, some of whom had caused others to experience the same loss I felt, helped me to find the closure I had not up until then found. Being around them helped me heal in so many ways. I think it was because I recognized that that they could never change the consequences of their actions. And they had to live with that and accept it. It was clear that they always carried the burden of their actions while taking accountability for having done whatever it was.

I realized that we can only move forward. These are people to whom hope and the future are paramount. That rubbed off on me somehow. I realized that we were the same in reversed ways. And I learned that until one recognizes the consequence of their actions and humanizes their victim, they cannot truly accept what they have done. Once that happens and I saw it happen and heard about it over and over in Lonnie’s program, that person will never hurt another person ever again. It’s interesting, you must embrace and understand the depth of your pain; only then can you actually live with it in a productive way. Observing them, I learned to do it with my grief.

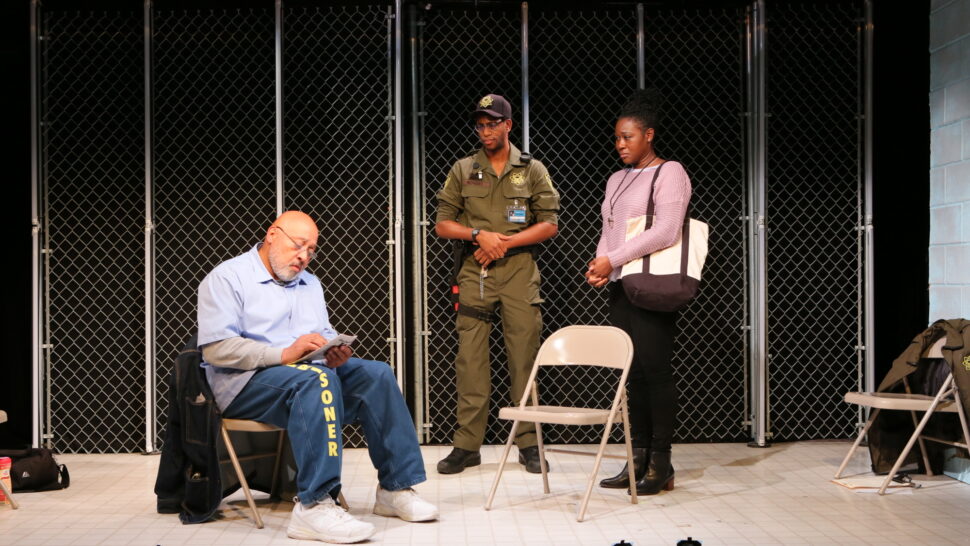

Eric Berryman and Zenzi Williams in "Lockdown" at Rattlestick Playwrights Theater. Photo: Sandra Coudert.

KATIE: Wow. So, LOCKDOWN focuses not only on the actual lived experiences of imprisoned folks, but your own life as well. It’s a play of undeniable truth. One line in particular that rings true is spoken by Wise: “Intelligence and education are not the same thing.” That stuck with me after reading LOCKDOWN, especially given the context in which it’s said. Why is this important for audience members to hear?

CORI: After volunteering for so long now at the prison and getting to know so many people they are literally like family members, it has become somewhat of a mission for me to do what I can to try to change the narrative of what prison is, and especially who the incarcerated people are. Some of the men I know who are serving long sentences began their time in prison at very young ages. Like Wise. I know a man who was 16 when he went to prison and is now 43. He was given a 54-to-life sentence. He barely went to school before going to prison. He could not even read or write when he entered prison. Yet I believe that he is a genius. He taught himself to do some of the most remarkable things.

While there are many super-intellectual, well-read and educated incarcerated people, there are some who are just street-smart and life-smart. In society we place a lot of importance on Ivy League schools and neighborhoods, brand names, etc.…but I know I have had conversations with some of the wisest, most intelligent people I have ever met, right there in prison. I wanted to point out that being book-smart is not the only kind of smart there is; that everyone has something they are good at and that when you listen to people instead of just hearing them, you can learn so much. I wanted to try to help the audience see that the breadth of intelligence that might reside within a person can be measured in ways other than a traditional education.

KATIE: “Everyone has something they are good at.” That’s hugely impactful. Now, outside of your writing career, you are also the founder of a non-profit organization, The Pa’s Hat Foundation. Can you tell us a bit about your experience creating this foundation?

CORI: I am a first-generation American-born child of two immigrants. My mom was Brazilian, and my dad was from Liberia, West Africa. He was Ambassador to the United Nations in 1980, and there was a coup’d’etat that overthrew the Liberian government and began a terrible long lasting war which didn’t end until 2006. Many people were killed, including an uncle and others I knew, and the new people in power wanted to kill my dad as well. We were living in the United States at the time, and my dad had to apply for political asylum, which was granted. Twenty years later, the year 2000, he was 83, the war was still going and he thought he might not outlive it. He wanted to visit his parents’ graves and decided to go to Liberia.

As the eldest child, I was ordered to go with him. Trust me, I did not want to go, but he was old and my mom said someone had to go with him. It’s a long story that I have written a trilogy of plays about: The Liberian Legacy Trilogy. Briefly, while there on this trip, a child soldier pointed an automatic gun at my head and I thought I was about to die. In fact, I very well could have. When writing the first play in the trilogy, “Pa’s Hat,” which is about this trip with my dad, and my encounter with almost dying, I had to step into the shoes of the child soldier who had pointed a gun at my head. Instead of anger, or bitterness, I felt only sadness and compassion. No child wants to go around killing people. Especially not these who were usually grabbed from home and trained to become killing machines. Eventually, after the war, I got to know a bunch of former child soldiers. Amazingly, all of them said that they wanted to go to school. I started the organization so that I could try to raise funds to send them to school. To date, I have put 6 young men all the way through school.

I am not great at running this organization by myself. In fact, right now, the website is not even working, and I have been trying to fix that. I did not know how to fundraise properly, so I never raised a lot, but I scraped and saved and did the best I could. I have also spearheaded a few other missions in Liberia geared towards helping marginalized citizens with education and help with work. But the 501c3 still exists, and I am hoping to fix the website and you never know. But Covid and just being busy here with writing makes it hard to do a lot with it. Still, the young men I put through school all call me “mom”. I am “Cousin Cori” at the prison and “mom” to the former Liberian child soldiers I put through school. I just realized that both these labels under these contexts make me feel pretty proud.

Read Cori's BIO HERE